Editor’s note: The following six stories were written by College News Workshops students at Columbia College Chicago after interviewing Columbia alum Vee L. Harrison.

By Michelle Meyer

Vee L. Harrison is a journalist who not only asks questions but finds answers. Her current mission is to boldly find a connection in the divide of racism in our country.

“Our entire country chooses to put a band-aid on the damage that has been done to Black and Brown communities,” Harrison said. “Because if we put a band-aid on it, we don’t have to admit that enslaving people & bringing people over to this country in 1619 was atrocious and violent and abusive. It’s only right that we talk about it.”

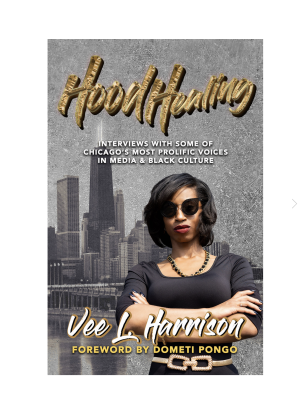

Now writing for Pigment International, Harrison does just that in her book “Hood Healing.” A collection of interviews with journalists and her own personal stories, “Hood Healing” offers solutions to the deep trauma the Black community has faced in Chicago.

Harrison looks for answers in all her journalism work and anticipates that trend to continue with future journalists. A Columbia College Chicago alumni, she visited a journalism class to share her experiences and answer questions. Harrison emphasized the importance of empathy the field requires in order to tell honest stories.

“Going into Black and Brown communities, that is something that the field has been lacking over the last few years,” Harrison said, adding that studying the communities and neighborhoods a journalist plans to cover is key to representing the truth accurately.

Photojournalist Mark Zoleta, echoes the same expectations for the industry. Zoleta, who has worked for news stations in Denver and Iowa, said he does as much research as possible beforehand to get the best representation of the people he covers.

“There’s certain reporters that seriously use every situation and people as stories and there are reporters that treat other people as people,” Zoleta said. He pointed out that this disingenuity is obvious to fellow journalists as well as the sources, allowing a comfortable space and being informed allows Zoleta to find that authentic human connection.

Correct representation behind the stories being told is also a necessary quality for accurate representation. As a Filipino photojournalist in a predominantly white area, Zoleta noticed his station in Iowa wasn’t locally covering the increase in Asian hate crimes during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“There are problems with diversity and equity in the newsroom and it does subconsciously affect decisions being made,” he said.

Both Zoleta and Harrison hold high respect for major quality journalists and their need for truth-telling stories – empathy. “You have to be grateful that they are sharing their experiences … This job can’t exist without the community around you,” Zoleta said.

“There’s a lot of social connection in journalism that has quite frankly changed my entire life,” said Harrison. “To be a journalist and tell these stories of other people is a privilege.”

###

By Abygail Garcia

Social media has become a more common place where people can get their news. With the convenience social media provides, nearly half of Americans 18 and up get their news from social media, according to a study done by the Pew Research center. Facebook’s the most popular choice, with nearly a third of American adults getting their news from the site.

Journalist Vee L. Harrison, has witnessed this transformation in news since she graduated from Columbia College Chicago in 2010. She refers to the new journalism as “mobile journalism,” because of how instant and how accessible it is.

“Holding your phone in your hand you can get literally a terrorist attack in your hand, and all details surrounding that terrorist attack,” she said.

One of Harrison’s first published stories covered the house party in the early days of the COVID-19 epidemic that took the media by storm in February 2021, in the Triibe.

When TMZ first published the story, they did not talk to the participants, but focused on the recklessness of those attending the party.

When Harrison reached out to Tink Purcell, a partygoer, Harrison said, “She was like, ‘Oh my God, you really want to interview me? You really care what I have to say, you really want to know why?’”

Through her reporting, Harrison learned that the party had been held to commemorate the death of a young man who had been killed due to street violence.

Suzane McBride, former chair of the Communication Department at Columbia taught Harrison in spring of 2010. During that time McBride and a colleague launched AustinTalks, a community news website that McBride continues to edit and publish.

Social media however isn’t the only change to journalism. Now that becoming a publisher is much more accessible, it’s easier for people to put out news from different perspectives.

McBride, now the Dean of the School of Graduate Studies, says that she wouldn’t have been able to run AustinTalks without the invention of the internet and that it’s been good in terms of diversity, equality, and inclusion.

Even with that accessibility, there’s still work to be done. The News Leaders Association has been conducting a diversity survey, which has taken a poll of race, ethnicity, gender and sexuality in newsrooms for over 20 years. However, due to lack of responses, they were unable to continue the survey.

But the fact that anyone can say anything is a double–edged sword. It’s much easier for misinformation to be published and spread, damaging the credibility of the field as a whole.

McBride said that for the average newsreader you need to be able to think critically and do your homework. If you don’t do that, you’re more likely to not be able to discern what’s truthful and what isn’t.

“I think sometimes there’s been a bit of confusion in recent years and not enough education on the part of journalists to explain this is factual information, it is not my opinion.” McBride said.

###

By Izzie Rutledge

Two Chicago journalists are taking aim at how the media covers Black communities in Chicago, citing that coverage often lacks a connection with the audience being targeted.

Freelance reporter, author and West Side native Vee L. Harrison said research and preparation are essential to this change. Harrison said one issue is that journalists who are not people of color don’t take the necessary steps before entering diverse communities.

“With all due respect, there are white journalists that go into Black neighborhoods who haven’t studied the neighborhood, who haven’t studied the people, studied the inequity,” she said while speaking to a journalism class at Columbia College Chicago where she earned her journalism degree in 2010.

Such care can often be overlooked, according to Harrison, but thorough knowledge of the background of people being reported on is necessary to credibility. She said journalism should go beyond surface level and serve to facilitate change.

“People love to talk. I do, but can we do something? It needs some serious movement. It just should not be a situation where there are young people who are getting killed on the side of the city and once we cover it with an article we don’t hear a solution anymore,” Harrison said.

Tonia Hill, a reporter for the Black-owned Chicago publication, The Triibe, said a way that journalists can improve their coverage of communities of color is to build relationships.

“I think one big thing is to just be listening to community members. Don’t just come in, you know, to write a story and then leave,” she said.

She continues that such relationships are important to the understanding of both writers and consumers of news.

“It feels like whenever these stories come out about these shootings that people are looking for a reason not to care about the person or the victim…Like I have to choose when I care about somebody dying because of whatever relationships or things that they did in their life,” Hill said.

Harrison said empathy is one tool journalists should have to better their writing and connection to communities, regardless of their race. She said that spending time in communities one is not familiar with is a good way to develop both connection and empathy.

“What has happened to Black and brown families over centuries in this country, the degradation and the pain, is going to take all of us to connect to get past, every single one of us,” she said.

###

By Elizabeth Rymut

After being raised in a culture of secrecy, and that still holds underlying trauma, it is revolutionary for Vee Harrison and her mom, Sandra, to now be sharing their experiences with outsiders.

Among people of color, especially African Americans, there has been a stigma created around talking about anything that was going on at home, Vee L. Harrison said. She remembers her own mom raising her this way. “Growing up Black in the inner city, it was super taboo to talk about your problems. It was this whole thing ‘don’t go telling what’s happening in momma’s house,’” Harrison said. Harrison was speaking to a journalism class at Columbia College Chicago, where she also earned her degree in journalism. She is now a working journalist.

This mentality and culture come from the lifestyle African Americans on the West Side and other similar communities had and have because of how that information would get passed along, Harrison said.

“A lot of people consider that old school. That’s how my mom’s upbringing was and that’s how her mom’s upbringing was. There’s this culture within the culture of not talking about people’s problems,” Harrison said.

In some households, something heard by word of mouth could get a child taken away from their parents, said Sandra Harrison, 57, mom of Vee L. Harrison. There’s an almost sense of urgency to protect the family from harm. “Oh, definitely it was common. You talk about getting beat and child services would be called to your home,” Sandra Harrison said.

Sandra Harrison had Vee, known as Veronica to her, when she was 17. While she didn’t know very much about parenting and raising a child from her upbringing, she knew one thing for sure, don’t talk about your problems.

“I was raised like that and I passed that on because I started raising my first kid [when I was 17,]” said Sandra Harrison.

Almost a year ago to the day, on Super Bowl Sunday of 2021, Sandra Harrison’s son, Darryl Harrison Jr., became a victim of gun violence.

With the movement started by her daughter to uncover trauma within the Black community and the death of her son, Sandra Harrison has learned to be more open about struggles she has endured. “I see now that it is becoming more acceptable to share that trauma and I see that it is necessary,” Sandra Harrison said.

###

By Natalie Zalewski

Vee L. Harrison is all about remembering her roots, so she reconnected with the root of her career in journalism. Harrison, who graduated from Columbia in 2010, returned to her alma mater recently to speak to journalism students about her experience being a Black journalist in Chicago and discussed her debut book, “Hood Healing.”

Harrison grew up on the West Side of Chicago, where she lived through a plethora of distressing situations she kept quiet about.

“All these stories inside of me, I knew I wanted to tell them, I just didn’t know if it was permissible,” she said. “Growing up Black on the West Side, there were so many things that we didn’t just talk about.”

Instead of internalizing the pain she endured, Harrison turned to journalism as an outlet to share both her own experiences and those of others. This served as the primary inspiration behind her debut book “Hood Healing”, a compilation of interviews with Black journalists opening up about topics such as generational trauma, the post-effects of slavery, and the disconnect between Black youth and the media.

In less than 100 pages, Harrison amplifies voices from those “who are usually telling other people’s stories, but are now telling their own,” she said.

“What has happened to Black and Brown families over centuries in this country, the degradation and the pain, is going to take all of us to connect to get past. So many times, we silence ourselves, when we really need to get a little louder.”

Sujay Kumar exemplifies Harrison’s point in his role as co-editor in chief at the Chicago Reader, where he shares personal experiences of both his own and his colleague’s struggles as journalists of color, specifically focusing on workplace discrimination.

“The Reader is a traditionally white male legacy publication; this means that when I became co-editor, I could sense that some staffers and ex-employees mistrusted me and thought I was a ‘diversity hire,’” he said. “That means that my skin color meant more to the hiring process than anything on my resume. Of course, my co-editor, a Black lesbian woman, experienced this far more intensely. I’d like to say there was a moment where we won over the staff, but really I just put my head down and focused on the work.”

Harrison’s main goal is to seek and speak the truth through her journalism. Her breakout article about a West Side house party being held during the height of the pandemic is a prime example of this, as she sought out the truth after multiple news outlets reported just one side of the story.

Through speaking with Tink Purcell, the woman who held the party, Harrison discovered the party was held to honor a friend who had died from gun violence; that is the information that initially was not being reported.

Harrison’s story then went viral; Triibe Magazine, a black-owned media outlet, reached out to offer her a position on their staff.

“When I unveiled the story, they were so impressed they asked me to be their general assignment reporter, and it was history,” she said.

In her advice to aspiring journalism students, Harrison continues to preach the importance of authenticity, both in reporting and writing.

“I believe that the revolution in journalism, and across this country, is going to be the people shouting the truth, who aren’t afraid to just tell it how it is,” she said. “If lies can be embedded in our country, so can telling the truth, being factual, and making people uncomfortable to do those things.”

Harrison’s book, “Hood Healing”, is currently available for purchase on Amazon, along with an audiobook version coming soon.

###

By Zoe Takaki

Ready to discuss her new book “Hood Healing” with a Columbia College Chicago journalism class, Vee L. Harrison, journalist and Columbia College Chicago alum, positioned herself confidently at the head of the table, her book eagerly sitting in her hands. The book is a nonfiction work that analyzes generational trauma and its effect on black people living in Chicago, Harrison’s hometown.

“One thing I wasn’t seeing was answers… I wanted a book of answers about trauma, to be quite frank. I wanted to know what was going on out there and growing up Black, like I said on the Westside of Chicago, so much of that was around me, but I had no answers,” said Harrison, speaking to a journalism class recently.

Often journalism can explain problems relating to injustices, but rarely does it offer answers to those problems, Harrion said, adding her “book is full of answers” to the questions that many people have wondered about generational trauma.

Harrison’s work is an example of solutions journalism, said Columbia College Chicago journalism professor Sharon Bloyd-Peshkin, defining it as “deeply reported stories that foreground the response to a problem” and those responses are “solutions oriented.” This writing is often one that focuses on social injustices, responding to problems like racism, classism, and sexism.

“Our entire country chooses to put a Band-Aid on the damage that has been done to black and brown communities,” Harrison said, “Because if we put a Band-Aid on it, we don’t have to admit that enslaving people and bringing people over to this country in 1619 was atrocious and violent and abusive. It’s only right that we talk about it.”

Harrison’s work in analyzing past government action and histories’ effect on racism is critical race theory, under the Merriam-Webster Dictionary definition of it as “concepts used for examining the relationship between race and the laws and legal institutions of a country.”

Teaching critical race theory has had its critics, some conservatives arguing that teaching it will cast a negative view of white people and increase trauma for people of color.

But Harrison’s work and solutions journalism does not allow these critics to stop them from exposing injustices, Harrison telling journalism students “journalism is about truth, giving the facts the way they are.”

While some critics argue that stories about injustices are traumatizing and too intense for readers, not wanting the victims of these stories to retraumatize themselves by reliving their events through writing, Harrison and Bloyd-Peshkin see a different response to solutions journalism, readers not being traumatized but instead being heard for the first time.

“Somebody who has lost a loved one to gun violence is not going to be surprised or traumatized to read a story about it,” Bloyd-Peshkin said. “They’ve already been through the trauma. But they will be really be helped by stories about advocates for gun control… getting guns off the streets.”

She further explains that “solutions journalism can play that kind of a role in healing rather than traumatizing,” making it a great way for all readers to be informed and aware of injustices.

Be First to Comment